| UK: industry stats – the growth illusion In September 2019 we wrote a blog titled ‘the myth of growth’, using UK data to show that gambling had not grown materially in real terms for twenty years. A lot has changed in five years: online gambling has grown by another 30% and lockdowns have transformed the way people consume entertainment in a lasting way. However, fundamentally nothing has changed: people are spending less on licensed gambling in Great Britain now than they were in FY19. There are a number of important reasons for this which should shape domestic policy and international comparison as well as UK-facing operations management.  The Gambling Commission’s annual industry stats for FY24 (to March) look optically robust. The top five online group operators, for which the Commission publishes monthly revenue each quarter, have continued to lose share as expected, meaning underlying growth was higher. In the more consolidated betting market, top-five (really 4) share loss was 0.7ppts to 86.7%, which meant betting licensees outside the top operators grew by 10% YoY while the top operators grew by just 3%. The difference in gaming was even more pronounced, with 3.0ppts of share lost to 67.5%, meaning gaming operators outside the top five grew by 20% YoY, vs. 4%. While there are some operational reasons for this difference in performance (biggest isn’t always most innovative and at least two of the top five have suffered from self-inflicted problems caused by weak leadership), we continue to believe that the biggest reason for the shift is an uneven regulatory landscape. In our view, the £5 slots limit which is now been brought in will help to level the regulatory landscape down (something many of the top five advocated for on the basis their performance against the black market wasn’t being judged), thereby pushing a material volume of future underlying demand growth into the black market. Stronger-than-visible growth concentrated principally into the gaming long-tail is a double-edged message for future growth and channelling therefore. UK online growth has accelerated into calendar 2024 (see Financial Update on Q3), in part because of comps but also because of a dangerously misunderstood phenomenon: the lag effect of money printing and inflation. It has been a while since a gambling operator tried to blame a ‘cost of living crisis’ on poor operational performance. The real reason for the 2022 economic shock (which had a negligible impact on gambling) was a hangover from frantic state money printing during lockdowns; these have now washed through, but average salaries in 2023 were 15% higher than in 2019 (note the gambling sector is not 15% bigger), broadly based salary increases are still coming through (c. +5%), while the government continues to use deficit spending to fund the public sector, adding to inflation risk going forward. When the economy was sclerotic, but inflation was consistently c. 2%, then 4% growth meant something; with inflation likely to remain volatile regardless of central bank predictions, absolute growth is far less relevant than relative growth. Largely due to wage increases and inflation, we expect high single digit growth for online gambling in the UK subject to black market leakage, but we expect a relative decline in gambling revenue – with landbased gambling bearing the brunt. FY23-4 marked a period of optical landbased recovery, with all landbased sectors except the struggling National Lottery in growth. However, while landbased sectors in total added a net £63m to Britain’s gambling industry (excluding pub gaming machines, likely down), online added £471m, or 88% of all growth. This is a clear case of channel shift at work in ‘frog boiling’ form: landbased sectors are relieved to see some absolute growth but are losing relative market share. Again, inflation is an enemy in disguse – revenue goes up as businesses become less relevant and more fragile. |

However, three long-term consumer demand trends are much more sticky than channel shift. However, three long-term consumer demand trends are much more sticky than channel shift.The first is that the National Lottery has failed to maintain early levels of consumer interests (note, now under new ownership). This has been compensated for in part by the strong rise of the Charity Lottery sector, but this is a complementary rather than competitive product: nothing can replace a well-run lottery in terms of mass market customer engagement. Second, is the slow rise of slots content as the digital experience proved more flexible and increasingly more appealing than Britain’s stunted landbased offer. The new online stake restrictions are likely stymie and probably reverse this trend, in our view. Third, is the consistency of betting: football has overtaken horseracing in absolute revenue (by only 15% in FY24 after a generation of predicted doom for racing from betting commentators who preferred opinion to evidence), but betting maintains remarkably consistent in terms of revenue mix over twenty-five years despite all the hype over growth.  The relative growth in slots has therefore partially mitigated the relative decline of National Lottery revenue to keep gambling expenditure as a proportion of Household Disposable Income relatively stable at c. 1% over 25 years (note, FY9 was low because of the implementation of the Smoking Ban, the loss of S16/21 machines, and the onset of a global recession). However, an underlying decline can be detected and if the National Lottery is not turned around then it is likely to become more visible, in our view. The relative growth in slots has therefore partially mitigated the relative decline of National Lottery revenue to keep gambling expenditure as a proportion of Household Disposable Income relatively stable at c. 1% over 25 years (note, FY9 was low because of the implementation of the Smoking Ban, the loss of S16/21 machines, and the onset of a global recession). However, an underlying decline can be detected and if the National Lottery is not turned around then it is likely to become more visible, in our view. For all the hype about a changing landscape, very little is changing in terms of underlying consumer behaviour other than channel shift. British consumers are, if anything, gambling less, albeit with revenue concentrated in a smaller number of participants. For all the hype about a changing landscape, very little is changing in terms of underlying consumer behaviour other than channel shift. British consumers are, if anything, gambling less, albeit with revenue concentrated in a smaller number of participants.The growth visible in the FY24 industry stats offers more to be concerned about than relief for a recently battered industry. For the British gambling industry to have a future that is not a story of increasingly pronounced relative decline temporarily disguised by inflation, it needs to achieve ‘just’ two things, in our view: ensure the legislative and regulatory framework keeps high value players in the licensed ecosystem; the opposite is currently being achieved (note, London has already largely lost a c. £150-300m annual high roller casino segment taxed at a marginal rate of 50% – sufficiently specialist to disappear largely un-noticed) create products that have genuine mass-market appeal (the Charity Lottery sector is the unsung standout success story here) These two drivers of industry sustainability sound simple, but they are proving dangerously elusive to deliver. UK: RET policy – money, money, money: why the levy is far from funny “What operators rightly hate being told is that they ought to be contributing more than they are to RG programs without being told what they are actually paying for. They then readily form the suspicion that most of their money is spent on the cost of employing an army of hostile public and quasi-public officials. These officials are then perceived as having as their primary concern not the alleviation of suffering but the retention or expansion of their own jobs. This in turn, can be suspected of leading to the proliferation of regulations that have little or no empirical basis.” Professor Peter Collins, 2003 The decision to impoae a safer gambling levy on licensed gambling operators in Britian is by far the most ill-considered of the policies contained within the previous British Government’s white paper on regulatory reform. It is also likely to be the most significant in the longer term, with far-reaching consequences for the functioning of the gambling market, harm prevention and policy coherence. In this article, we set out why we believe the levy is bad policy, what its outcomes are likely to be and how some of its worst consequences might be mitigated. Why the levy is bad policy The imposition of the ‘safer gambling’ levy has been dressed up by proponents as self-evident. After all, what could be more reasonable than requiring gambling businesses to fund the treatment of people suffering gambling disorder as well as work to better understand harm and to prevent its occurrence? The polluter, as the trope goes, should pay. The problem is that is not how our society works. In the normal world, businesses pay taxes at rates set by HM Treasury, which are used to fund public services, including healthcare, research and education. Charities, community groups, and private businesses address gaps in what the state is prepared to fund. The safer gambling levy breaks this model by requiring treatment and other costs to be funded directly from the expenditures of gambling consumers. In so doing, it sets a precedent for levies to be funded against general retail businesses (to recover costs from compulsive buying behaviour), internet providers (internet use disorder), coffee shops and teahouses (caffeine use disorder), pubs and bars (alcohol use disorder), and restaurants (obesity) among others. Followed to its logical conclusion, it proposes a healthcare system paid for by citizens according to their lifestyle choices. There is a dark and unsettling logic to this if applied consistently – but no obvious justification for its imposition on gambling consumers alone. Combined with the draft guidelines of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the levy will make treatment providers dependent upon the NHS through the stipulation that they may not seek funding or engage with gambling businesses – effectively penalising those organisations that support the current regulations. One consequence of this model is that – contrary to the spin – the levy increases the dependence of treatment and harm prevention providers on the industry (as a number of public health figures have already observed). In replacing a voluntary system of funding with a tax, the government will tie financing to industry revenues. If consumer spending with licensed operators reduces, so will funding. Organizations lobbying for tighter restrictions on gambling consumers (or higher taxes on operators) will do so in the knowledge that new measures may negatively impact their own finances. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport has forecast a net market contraction of 8.2% as a result of its white paper reforms but this is speculative, and the impact could well be greater (particularly if modernising reforms for landbased operators are delayed). There is a very good chance that the levy brings in less than expected, which would be a major problem if the levy was underpinned by an actual budget or assessment of need. The levy has been justified by reference to two factors: concerns over the perception of research independence under current arrangements (regardless of whether those perceptions are grounded in fact)the fact that some operators have contributed derisory amounts under the voluntary system The first suggests that government policy is now dictated by perception (which is in turn influenced by lobbying) rather than actual evidence. The second is a red herring – no gambling business of any scale has been guilty of under-funding; and the parsimony of the few is poor justification for the creation of a new tax, although it does justify targeted intervention. The levy is also likely to be wasteful. HM Revenue and Customs already collects c. £3.5bn in specific gambling duties (in addition to general taxes less Output VAT) from the gambling industry, under direction from HM Treasury. The levy, however, envisages the establishment of an entirely new tax system, designed to collect roughly £100m under a non-fiscal authority, overseen by a levy board. While a Levy Board works well in racing, it is independently supervised with formal betting input (a board seat) and levy collected pays for clearly defined common interest objectives, neither of which apply to the safer gambling levy (although they could). Without these governance guard rails, the potential for waste, error and fraud is enormous, in our view. The suggestion that the levy Is ‘smart’ appears to be Ir of those Orwellian conceits that has come into vogue in recent years (such as the idea recently expressed in the Lancet that state control is freedom). The logic for determining who pays what – including the exemption of the National Lottery – appears non-existent beyond the results of a sector and product popularity contest among the levy’s engineers. The application of a 1.1% rate to online gambling is justified by the idea that: i) it is associated with higher rates of ‘problem gambling’; and ii) remote operators have lower operating costs. The first is solely true of online gaming and is not true for betting – the ‘problem gambling’ rate for online sports bettors in the most recent Health Survey for England was just 1.2% (albeit it is dangerous to leap to causality given that PG rates are principally set by a product’s popularity). The second is true for some remote operators some of the time – but not for the many others: plenty of landbased businesses have higher margins than plenty of online businesses and the channel has little to do with the outcome. More generally, the suggestion that efficiency should be penalised hardly fits with the Government’s growth agenda. There is a reason why tax policy is generally set by finance ministries and not by regulators. Ironically, based on the premise that online gambling operators are able to pay more because of higher margins, they should be able to offset any margin-reducing tax increases with a reduced Levy rate, though we doubt the logic will be applied so robustly. The levy is not so much smart as unfair. To provide one example, operators of gaming machines in bingo clubs and arcades are required to pay; but pubs and social clubs providing precisely the same machines are not. Further, the way that the Government has presented the tax is misleading because it is levied on suppliers (at 1.1%) as well as B2C operators (at between 0.1% and 1.1%). The effective rate of the new tax will therefore be applied inconsistently and at rates higher than claimed since we do not believe a recoverability mechanism (ie, the way VAT works outside the gambling sector) has been proposed – and it would make no sense if it did since gambling suppliers exist to serve gambling customers, who are being taxed through gambling operators. There is an additional irony that this highly complex levy, with multiple and arbitrary rates across different gambling products and channels, comes as the government simultaneously seeks to copy another of the previous government’s soundbite-driven schemes, since it will: consult next year on proposals to bring remote gambling (meaning gambling offered over the internet, telephone, TV and radio) into a single tax, rather than taxing it through a three-tax structure. This will aim to simplify, future-proof and close loopholes in the system. Perhaps someone needs to tune the governments’ wireless. What can we expect next? It has been claimed that the ‘safer gambling’ levy will result in greater resources and more certainty for harm prevention services, which would be a good thing. It will probably (depending on events) bring in more money than under the voluntary system; but that is not the same thing. For one thing, it will involve the creation of new administrative bureaucracy for which no published budget exists (a major lacuna) and, given the way that the state spends money, is unlikely to be either modest or well governed. Half of the funds left over after as yet unknown administrative costs will be allocated to the perennially over-stretched National Health Service, which will almost certainly prioritise its own services over the requirements of the Third Sector. The charities, who have in some cases been effectively and diligently providing treatment to people with gambling disorder for more than half-a-century, will now be required to bid for the funds that were previously theirs. Several harm prevention organizations have already started to shut down programmes (including training for licensees) and making members of staff redundant (up to 150, if reports are correct). Made dependent on the state, treatment providers may find that they are required to fall in line with radical public health ideologies, such as the belief that adults bear no responsibility for their actions and harm is solely the result of exposure to ‘addictive products’. This denial of human agency breaches a core tenet of psychotherapy and has the potential to cause enormous damage to vulnerable people by institutionalising victimhood. A further 30% of net funds will be allocated to the conveniently vague domain of ‘harm prevention’. Rumour suggests that the commissioner will be either GambleAware or OHID. The former has already called for mandatory health messages on all gambling advertisements (including for the National Lottery and horseracing); while the latter has manufactured suicide statistics and proposed ‘plain packaging’ (no colours, logos or images) for all gambling products. GambleAware may be slightly less illiberal than OHID, but both have trouble distinguishing between harmful gambling and gambling – a blind spot that ultimately leads to long-term prohibition via a medium-term funding bonanza. We can only imagine what they might get up to with up to c. £30m a year. The final 20% is allocated to research under UK Research and Innovation (‘UKRI’). It is to be hoped that UKRI demonstrates greater scientific rigour and moral neutrality in commissioning research than the Gambling Commission, GambleAware, or OHID. The risk, however, is that it becomes a slush fund for anti-gambling activism that will be used not just in Britain but internationally to campaign for the prohibition of gambling once all the funding that can be extracted has been. In recent years, a profusion of clearly agenda-driven journal papers and reports of low academic quality have been published – often as a consequence of Gambling Commission or government funding – alongside a very small number of high-quality studies. There is a risk that the levy will be used to fuel a propaganda engine for an international anti-gambling movement. The reason why activists have prioritised the levy above all other matters is because they know just how large the prize is – up to £20m per annum. For all the high-minded rhetoric, the levy seems destined to result in disruption to treatment services, increased stigmatisation of gambling as a legitimate adult pastime, and the production of misinformation on an industrial scale which politicians and bureaucrats seek to lack the discipline or inclination to critically assess. What should be done now? The safer gambling levy may be bad policy, but it is now policy, and it will come into force next year. The question is therefore what ought to be done by licensees and others. We make three suggestions: Governance – there is a good chance that money raised by the levy will be used inefficiently, unscientifically and inappropriately. The process for how funds are allocated and assessed therefore requires close public attention. Scrutiny should be applied to the levy’s governance arrangements and the process of evaluation in 2030. Given what has gone before, it would be naive to trust those responsible to mark their own homework Continued support – a large number of harm prevention organisations now face uncertain futures. It would be a mistake, in our view, for operators to cease their support for charities and other harm prevention organizations once the levy kicks in even at the cost of ‘paying twice’. Several important programmes now face defunding (in addition to those that have already fallen by the wayside); and operators need insights from these groups in order to inform their own ‘safer gambling’ initiatives – for the sake of disordered gamblers and the sustainability of effective treatment, a distinction must be made between the sunk cost of a pollicised levy and productive expenditure on mitigating the harms that the licensed gambling sector does cause or exacerbate Critical analysis – the levy is likely to result in an expansion of anti-gambling activism, particularly in the domain of ‘research’, which will reach into other jurisdictions. To date, the licensed gambling industry in Britain and other jurisdictions has done an extremely poor job of assessing and (where appropriate) rebutting bad science. It is critical that it develops both the technical capability to scrutinise research and the willingness to call out misinformation (including misinformation which seems to support the industry). There is a good case to be made for building this capability on an internation basis.Ironically, the new levy is at least in part the unwitting handiwork of some of the largest licensees in Britain’s gambling industry whose lobbying made the policy almost inevitable. The Betting and Gaming Council’s endorsement of the policy was unfathomable to us at the time and continues to be so; it makes a lobbyist’s job much easier in the short-term but the industry’s job far harder in the long-term. There is a lesson here which the industry should now be able to perceive – policymaking is difficult in this space; and the pursuit of easy fixes is liable to end in disaster. Unfortunately, the government may have to wait a little longer before it arrives at this epiphany. Regulus partners |

| Disclaimer; The analysis provided in this report represents the opinions of the authors. Any assessment of trends and change is necessarily subjective. The information and opinions provided herein are not intended to provide legal, accounting, investment or policy advice, nor should they be used as a forecast. Regulus Partners may act, or have acted, for any of the companies and other stakeholders mentioned in this report. |

Tag: news

Abusing NHS statistics

UK: ‘We don’t need no thought control’ – why the Gambling Commission should leave NHS stats alone

In recent years, the Gambling Commission has been on the receiving end of criticism from all sides of the so-called gambling debate. Last year, the MP, Sir Philip Davies declared that the regulator was “out of control”, while the Social Market Foundation has described it as “not fit for purpose”. The Commission has not publicly endorsed either of these views – or advertised them on its website – presumably because it considers them to be untrue as well as unflattering. Last month, however, the Betting and Gaming Council (‘BGC’) was asked by the Commission to make claims about the prevalence of gambling harms which are probably false – and to publish them on its website.

In an email recently released under the Freedom of Information Act, the Commission wrote:

“We’ve been keeping an eye on use of GSGB [Gambling Survey for Great Britain] data and use of figures as the official statistic. We’ve noticed that BGC still refers to previous stats, it’s not a misuse of stat issue but we’d be keen for you to start using the official figure moving forwards.”

This invitation was politely declined by the BGC on the grounds that it has greater confidence in NHS statistics (which are accredited by the UK Statistics Authority) than in the Commission’s (which are not). The BGC is similarly unlikely to profess that its members are (to borrow from Blackadder) ‘head over heels in love with Satan and all his little wizards’; but the Commission can always try.

The regulator’s entreaties should be considered in the light of the following circumstances:

i) the balance of evidence indicates that the GSGB substantially overstates levels of gambling and gambling harm in Britain

ii) the Gambling Commission knows this

iii) in asking the BGC to go along with the charade, the Commission is acting, at best, inconsistently

iv) the GSGB is already being used (and misused) by activists, seeking to reopen the Government’s Gambling Act Review.

We examine each of these points in turn.

1. The balance of evidence

The GSGB may be the new source of official statistics, but this does not mean it provides a reliable picture of gambling prevalence in Britain. To believe that it does, it is necessary to subscribe to the following:

i. Every single official statistic on gambling and harmful gambling produced over the last 17 years – by the National Health Service (‘NHS’), the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the Gambling Commission itself – has been substantially wrong

ii. The NHS has serially misreported the prevalence of health disorders in general – and continues to do so

iii. Audited data on actual customer numbers using licensed operators is incorrect (or there is a massive black market that failed to show up in previous studies and of which the Commission was previously unaware)

iv. The opinion of the independent review (conducted by Professor Sturgis of the London School of Economics) that the GSGB may substantially overstate true levels of gambling and gambling harm is misguided

To believe that all these things are true (and to cajole others into professing the same) requires more than blind faith and a sheriff’s badge. Tellingly, the Gambling Commission does not have very much confidence in the GSGB itself; and has issued guidance that key results should be used “with some caution” or not at all.

2. Withholding evidence (again)

The Gambling Commission’s defence of the GSGB has largely consisted of attacks on NHS statistics, claiming that they have under-reported rates of ‘problem gambling’. While scrutiny is important, undermining accredited official statistics on health is a step not to be taken lightly. Some sort of evidence is required. For this, the Commission has relied upon a 2022 study which claimed social desirability response bias (ie, the fact that people sometimes answer survey questions in what they consider to be an acceptable rather than accurate fashion) caused under-reporting of ‘problem gambling’ in NHS surveys. This ‘evidence’ was thoroughly debunked by Professor Sturgis as part of his independent review – but for reasons known only to the Commission, the analysis was suppressed. It required a Freedom of Information Act request to secure the release of the information. This is not the first time that the Commission has prevented publication of critical evidence – having previously withheld survey data on customer opposition to affordability checks. Disclosures also reveal the Commission was warned by its lead adviser, Professor Heather Wardle, that social desirability response bias was likely to be a “marginal factor” in explaining differences between the GSGB and Health Surveys (and that the dominant factor of topic salience bias resulted in over-reporting in the GSGB).

3. Two-tier thought policing?

In recent years, various parties have taken highly selective approaches to the use of ‘problem gambling’ statistics – often ignoring official estimates in favour of more convenient alternatives. Last year, the National Institute for Economic and Social Research did so in a report funded by a Gambling Commission settlement – using a rate two or three times higher than the official statistic. There is no suggestion that the Commission objected to this. In public consultations, the Commission itself relied on ‘problem gambling’ prevalence rates from the 2018 Health Survey for England rather than lower figures from the 2021 edition (ie, the official statistics at that time). In a speech in Rome last month, the chief executive of the Commission, Andrew Rhodes criticised those who wished to “turn the clock back” to previous official statistics, and in the very same speech cited participation estimates from ‘previous official statistics’.

4. The weaponisation of research

The importance of all of this has been amply demonstrated in recent weeks. Both the Institute for Public Policy Research and the Social Market Foundation cited the GSGB’s inflated rates of ‘problem gambling’ in support of demands for ruinous and self-defeating tax rates (as high as 66% of revenue); while GambleAware has used the survey findings to call for tobacco-style health warnings to be slapped on all betting and gaming adverts (including those for the National Lottery). The Commission appears, therefore, to be encouraging the use of inaccurate statistics on gambling harms in the knowledge that they will be used in support of an anti-gambling agenda.

Perhaps Sir Philip had a point after all…

REGULUS PARTNERS NOVEMBER 2024

Speed Kills!

The British Horseracing Authority is committed to a reduction of fatalities in the sport of horse racing. To that end they have embarked on a number of initiatives to achieve that end

I want to focus on the National Hunt. An area that once again hit the headlines with the loss of 3 horses over the weekend at Cheltenham. Two appeared to be post race heart events. I’m told these are not attacks as we understand them. Both of these took place over the chase course, in the same race. One other horse fell in the Greatwood Hurdle and died

The time of this chase event was the fastest chase of the day. It was as quick an event as I’ve seen, and I’ve verified this view with other form judges. These days it has become a rarity to see horses actually fall in horse racing, it seems to have become unacceptable, even if the sport is supposed to revolve around jumping ability, and clearly that’s what people pay to see. I observed at Cheltenham, whilst reviewing races, how horses clear fences at this premier racetrack with ease. Often several feet above the birch.

This was also readily apparent in the 2024 Grand National, where the fences have been lowered, softened and landing areas eased, to such a degree that no horse fell in the entire race. What is of most note is horses no longer bend, or arch their backs to jump. They clear fences with speed undiminished. The first fence is fairly infamous for speed based falls, as the 40/34 strong field would be at their quickest at that stage.

Whilst the BHA, under Nick Rust embarked on a programme of overall diminution of fence heights and stiffness, the fatality rate in the Grand National is currently running equal to the highest percentage rate ever. Without comment from the BHA. Since the 1960s 29 horse fatalities have occurred where ground is either good or better than good. 43 if we include good to soft. Just 5 have died in ‘heavy’ ground, and no horse fatalities were registered when ground is officially ‘soft’

Of further note, long term injuries have increased in the sport for the 4th year in a row since 2020. The lowest rate of fatalities? In 2020, when the winter was the wettest on record

With these facts in mind, is the BHA approach gaining the required results? To me their approach is centred upon optics. Where they have defined form! If we have fatalities, make the test easier has been the code

I would argue their approach focusses on the difficulty in jumping hurdles, or chases, when they should be focussed on ground, and speed. In simple terms the horses have quickened up. This is the inevitable consequence of making the obstacles easier

When the Grand National fences were at their fiercest, in the 1960s, just 2 fatalities were registered. Can the BHA explain this? Anyone who wandered around the track in the 3 or 4 decades since then, could only have been impressed by the scale of the fences. It was what people tuned in to see. The BHA’s approach in my opinion has been naive on two fronts. It increased the rapidity of racing, and it made the sport’s showcase less compelling to the viewing public, as evidenced by television audiences worldwide

This is what happens when you allow a betting executive free reign to mess about with the sport, with optics as his focus. I recall his comments on the heavy ground 4 miler at the Festival, where several horses finished notably tired and jumping became ragged. There were no fatalities in that race, but the race was identified by Rust as having ‘more fallers and horses brought down.’ Hardly surprising at Cheltenham’s longest chase event! It became clear that Nick Rust’s epitath was to nailed to his views on horse welfare. He reduced the race by a quarter of a mile and questioned the participation of the amateur riders involved.

One final point, before I leave you to discuss these points. Remember Cheltenham’s ill fated 3rd last fence? A notorious obstacle, not because it was taxing, but because it was at a critical downhill part of the track, where horses were speeding up. They tended to overjump, and collapse with fatigue on the landing side.

Make me the CEO of British Racing – I would increase the height of fences once again, and their stiffness. Force horses to slow down several times a race. I would demand tracks water more assiduously in the winter to produce soft ground. I would do everything possible to slow these impressive animals down. Speed is the killer in British Racing. Not the difficulty of the obstacles they face

The Chancellor would be wise not to kill one of Britain’s few remaining golden goose industries

“I know we cannot tax and spend our way to prosperity.”

These were the words of Chancellor Rachel Reeves to the business community ahead of this week’s International Investment Summit. This was an event she championed as a way to try and promote growth.

I cannot agree more with those sentiments. But taxing business to the point of oblivion will hobble growth, not deliver it.

The Betting and Gaming Council (BGC) members I represent annually generate £6.8bn into the economy in gross value added, according to figures compiled by EY. They raise a further £4bn in tax for the Treasury, while supporting 109,000 jobs.

This is a huge business, with around 22.5m adults in the UK enjoying a bet each month. The overwhelming majority of them do so safely and responsibly. It is part of our British heritage and culture as well as a bastion of the leisure and entertainment sector. It has made our members – companies such as Flutter, Entain, evoke, Bally’s and bet365 – global leaders, generating billions for the UK.

Crucially, these are not just London-centric operations. Our members have headquarters in Stoke-on-Trent, Newcastle-under-Lyme and, as the Chancellor rightly recognised, in her very own city of Leeds.

We have always been clear that proportionate regulations and a stable tax regime are the only foundations which can deliver on the Chancellor’s ambitions. In order to continue to invest and grow, our members need confidence and stability. Both have been in short supply in recent years.

When the previous government finally published the Gambling Act Review white paper, the BGC welcomed the balanced and proportionate measures it contained.

However, there is no sugar-coating the reality: it will cost our sector well over £1bn a year in lost revenues once all the measures are implemented. It includes a new tax in the form of a statutory levy of £100m a year to fund research, prevention and treatment services to tackle problem gambling – an issue the NHS’s Health Survey for England has confirmed affects just 0.4pc of the adult population.

As we wrestle with those seismic changes, the last thing we need is a further tax rise being demanded by anti-gambling campaigners. They gleefully claim that increasing taxes as high as 50pc will raise billions for the Treasury, while having zero impact on businesses, jobs or key sports we fund such as horse racing. It’s fantasy economics and they know it. Any tax rises now, of any scale, will land a hammer blow to one of the Chancellor’s few growth sectors.

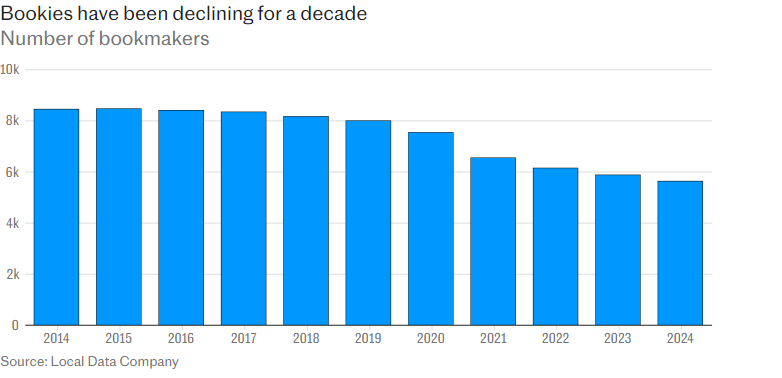

Contrary to the cries of campaigners, betting and gaming is not a soft target. Putting up taxes or imposing draconian regulations does huge damage to businesses. For example, recent regulatory changes directly contributed to 2,485 bookmakers closing since 2019 – a 28pc reduction with the loss of over 10,000 jobs and the business rates they generated.

You cannot put “rocket boosters” under sectors such as ours, as Liz Kendall, the Secretary for Work and Pensions, said at the Investment Summit, while also slamming the brakes on our industry with tax hikes and changes which drive customers away.

The pain is also not restricted to our members, it directly hurts sport.

Horse racing is the most obvious. The affordability checks – a construct totally unique to betting – has hastened double-digit percentage declines in betting turnover, effectively making it close to a loss-making product for some of our biggest members.

Football, especially in the lower leagues as well as in rugby league – a sport much lauded by Lisa Nandy, the Culture and Sport Secretary – along with other working-class sports, such as snooker, darts and boxing, rely on the income betting delivers. Hit betting and you will hit sport, from the grassroots to the elite level.

There is another issue blithely ignored by armchair economists, the growing threat of the unsafe, unregulated black market. A recent study found 1.5m Britons stake up to £4.3bn on this gambling black market. These operators offer deals too good to be true, circumventing the crucial player protection tools standard across BGC members. They also don’t pay tax, don’t create UK jobs and don’t support sport.

Rachel Reeves is right to go for growth. So it would make no sense whatsoever in the Budget to over-tax a gambling industry which has been hit hard by the Government in recent years. We want to play our part in investing and helping to grow the economy. The Chancellor would be wise not to kill the goose that is already laying the golden eggs.

Grainne Hurst- Betting and Gaming Council CEO

From the Telegraph

The moral collapse of the gambling commission

Great Britain: Regulation – the moral collapse of the Gambling Commission

For those with an inclination to learn, this week’s events offer the Gambling Commission a valuable lesson in authority. The market regulator exercises a coercive authority, mandated by Parliament, over anyone who holds a licence to provide betting or gaming services in Great Britain. Where others are concerned, it must rely on moral authority – but this commodity has been all but exhausted by its own actions.

In an open letter to the Prime Minister published on Monday, a succession of activists, politicians and researchers (categories that have become increasingly indistinct), openly flouted the Commission’s authority while the ink was still dry on its guidance for how results from the Gambling Survey for Great Britain can and cannot be used. In what can only be considered a triumph of hope over experience, the Commission had promised that the issuing of its guidance document would curb the tendency of campaigners to misuse Official Statistics; but the Peers for Gambling Reform (‘PGR’) letter to Sir Keir Starmer (or ‘Sir Kier’ as these Peers appear to have dubbed him) showed this trust to be misplaced. The GSGB is not due out until this morning – but the signatories to the open letter jumped the gun by referring to “a higher picture of gambling harm than existed previously” (a claim that contravenes the guidance regardless of its attribution to the former minister, Stuart Andrew MP).

The role of gambling market regulator is a difficult one – but the Gambling Commission has made its task needlessly troublesome by playing politics. As articles in the Racing Post and elsewhere have revealed, the Commission has in recent years suppressed evidence, manipulated surveys and facilitated the funding of anti-gambling activism through the disbursement of regulatory settlements. As the journalist Christopher Snowdon has observed, the Commission’s decision to publish misleading prevalence statistics while at the same time telling people to ignore them for the purposes of estimating prevalence is irresponsible: “They’re your statistics. Take some responsibility”, he wrote last week.

It is rumoured that at least one media outlet has refused a Gambling Commission request to amend its reporting of the GSGB. In any case, belated corrections on an obscure clarifications webpage provide scant redress for the impact of misleading headlines.

The PGR letter was revealing in other ways. In demanding the imposition of a safer gambling levy, the signatories claimed that “it is widely understood that the statutory levy would give oversight of treatment funding to the NHS, research funding to UKRI and prevention funding to OHID.” The DCMS has stated its intention to allocate commissioning responsibilities to the NHS and the UKRI but has made no such announcement with regard to the OHID, so it is unclear where the PGR is getting its information from. The appointment of OHID to the role would probably spell the beginning of the end for the licensed betting and gaming market in Great Britain. Officials at the department have indicated a desire to impose tobacco-style controls on operators and consumers; and have proposed annual increases in duties (effective prohibition), total bans on advertising and even – as bizarre as it may seem – ‘plain packaging for all gambling products (“no colours, logos or images”). They have shown a willingness to manufacture statistics and mislead policy-makers in support of this ambition.

It has been suggested on social media that the Good Law Project complaint about GambleAware (whose moral distaste for gambling pales by comparison with the OHID’s illiberalism) was designed to knock the charity out of the running to be the prevention commissioner. The Charity Commission’s rejection of the complaint (announced this week) should prompt an investigation into potential wrong-doing by those who involved (including whether the OHID had anything to do with it). Scrutiny of charities is important but requires care. Spurious accusations designed to disrupt the activities of the Third Sector is unacceptable. The Gambling Commission may not be the only ones to discover how quickly moral authority can erode.

Text book misconduct in public office

Primed Numbers: exercises in policy-based evidence-making?

Last month, the Racing Post revealed that the Gambling Commission had withheld for more than three years, evidence of widespread consumer opposition to affordability checks. The story raised a number of questions – from legal experts and others – about how evidence is used to inform regulation. In particular, it prompted speculation about why the market regulator was able to claim a consumer mandate for the imposition of checks when the weight of evidence tilted so clearly in a different direction. In this article, we examine the Gambling Commission’s use of consumer research on affordability checks, how survey responses can be stimulated to achieve the desired effects and why we should be wary of policy-based evidence-making.

The evidence trail starts in 2019 when the Gambling Commission asked the research firm 2CV to investigate consumer attitudes towards the prevention of ‘binge gambling’ episodes. The results of this survey indicated considerable antipathy towards hard interventions with more than 70% of respondents rejecting operator-imposed controls (with one-quarter selecting no action whatsoever).

The Gambling Commission omitted these findings when it published the results of the 2CV study and they were also excluded from the 2020 call for evidence on affordability checks, despite clear relevance. The results of the Gambling Commission’s ‘mini-survey’ in 2021 were even more stark. While three-quarters of respondents (most of whom were online bettors) agreed that operators should be required to take action to support vulnerable customers, 78% rejected proposals for affordability checks, citing consumer privacy, consumer freedom and their likely ineffectiveness in preventing harm. Just 14% of respondents stated that they would comply with checks while two-thirds said that they would feel uncomfortable being subjected to assessments by Credit Reference Agencies (‘CRAs’).

As the Racing Post has reported, these results were kept under wraps for almost three-and-a-half years and were deliberately excluded from the 2023 consultation on Financial Risk Assessments (‘FRAs’). In October last year, the Commission refused a request under the Freedom of Information Act (‘FOIA’) for the survey findings to be released, claiming that it would be too time-consuming to do so and that it saw “no outstanding public interest” in making them while the consultation was open. In February this year, the chief executive of the Commission, Andrew Rhodes, gave a personal pledge that the results would be published. The Commission however, failed to publish the survey results when plans for FRAs were announced in May; and it took a further FOIA request to finally force its hand.

By this point however, the Gambling Commission had released the results from a third survey (a self-selected online panel managed by the polling firm, Yonder); and this time the results were rather different. A large majority (78%) of respondents agreed that checks were “necessary to protect people from gambling harm” and just 6% disagreed. It is true that the 2023 survey related to a modified form of the affordability checks proposed in 2021 – but this seems an unlikely explanation for such a change in views on checks and the use of CRAs in particular (see chart). Is it plausible that consumer attitudes should have altered so dramatically in just two years?

| Survey | Sample size |

| Gambling Commission 2021 | 12,124 |

| Yonder 2023 | 1,000 |

There are two strong contenders for explaining why the Yonder panel yielded such different views from the 2019 2CV survey and the Commission’s own ‘mini survey’ in 2021. The first relates to sample composition. The 2021 survey was responded to by people interested in the issue of affordability checks – people who had sufficient skin in the game to take the trouble to respond. The Yonder panel by contrast, consisted of people who get their kicks (as well as some small financial compensation) from taking part in surveys – but who otherwise might have little interest in the policy (only 14% had personal experience of affordability checks). It is easy to be supportive of controls imposed on others.

The bigger issue however, is likely to be one of response priming. Prior to completing the 2023 survey questionnaire, panellists were exposed to ‘stimulus packs’, including ‘video stimuli’ to “maximise engagement and efficiency”. They were informed that the checks being consulted on were already Government policy and that they would “protect the most vulnerable while allowing everyone else to enjoy gambling without harm”. They were then shown a selection of newspaper headlines, with the explicit intention that these should affect (or stimulate) responses. Some of these headlines reflected concerns about checks while others warned about delays to implementation; but the overall impression was far from balanced.

One of the headlines told respondents that “Gambling addicts will die because of delay to reforms, government warned”; another that “‘There will be more people dying’: mother whose daughter took own life criticises gambling white paper”. In other words, survey participants were encouraged to believe that people would take their own lives if the checks were opposed. They were also exposed to headlines expressing opposition to checks (e.g. “MP urges racing to make its case against ‘crippling’ Gambling Commission proposals”) but such concerns will pale when juxtaposed against self-harm. Viewed in this light, the Yonder panel’s strong support for FRAs appears distinctly unsurprising. The second of the two ‘suicide headlines’ in the stimulus pack did not even relate to affordability checks but instead to advertising; and in fact rejected the idea that “even stricter versions” of checks would prevent loss of life (suggesting that survey respondents were not simply led – but actively misled). A third headline related to a comment piece in The Times written by a director at the activist group, Gambling With Lives; while the author of the fourth is understood to have connections with the same organisation.

Reviewing the stimuli to which the Yonder panellists were subjected, it is difficult not to be cynical about the Gambling Commission’s intent. Having failed on two occasions to obtain the desired response, the Commission left nothing to chance with the Yonder survey. Even if we ignore these issues and take the 2023 Yonder survey at face value, it does not explain why the Commission repeatedly refused to publish the results of the 2021 ‘mini survey’ (or the 2019 2CV study). The Commission’s selective use of evidence is difficult to justify – and so far it has made absolutely no attempt to do so. Its silence in the face of serious concerns about consultative process appears evasive rather than dignified. If it has reservations about the 2019 and 2021 surveys, it should explain what these are and allow people to make up their own minds about their value. Suppressing inconvenient evidence serves only to undermine confidence in the regulatory process.

In around six weeks from now, a pilot scheme to assess the viability of Financial Risk Assessments will commence; yet the Gambling Commission has still not published details of how this will be evaluated. The criteria for success have not been released and it is unclear how the integrity of the tests will be assured. Having spent the last three-and-a-half years agitating for checks, the Commission cannot be considered a neutral actor; and its reputation for impartiality has taken a battering of late. In the absence of a proper explanation for the withholding of evidence and a commitment to transparent evaluation of the pilot, the market regulator faces the threat of fresh controversy – and possibly legal challenge. It is unlikely that the incoming Culture Secretary, Lisa Nandy, will thank the Gambling Commission for such an avoidable headache.

Unreliable Suicide Claims in Gambling: ABSG’s Questionable Stance

The Great Suicide Deception. Part III – Conspiracy of Silence

Dan Waugh, Regulus Partners. May 2024

The Great Suicide Deception. Part III – Conspiracy of Silence

This is the third in a series of articles examining claims made by state bodies in England about rates of suicide associated with ‘problem gambling’. In the first we demonstrated that estimates of suicide mortality produced, first by Public Health England (‘PHE’, 2021) and then by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (‘OHID’, 2023) were irretrievably flawed. In the second, we looked at the behaviour of PHE and OHID, finding indications of a priori bias or inexplicable negligence and unsound governance. In this third article, we examine the conduct of others in positions of authority and ask why so many people who knew that PHE and OHID’s claims were unreliable decided to look the other way. We also recognise those who were prepared to apply critical analysis. Once again, we observe that, while gambling disorder has been recognised as a risk factor for self-harm for more than 40 years, efforts to tackle this are unlikely to be advanced by the use of junk science.

1. Why did the Gambling Commission not ‘do the right thing’?

By April 2022, Britain’s Gambling Commission knew that estimates of suicide mortality published by PHE were “unreliable” and based on “inaccurate” assumptions. This may have been a somewhat uncomfortable finding, given that the regulator had previously described the review as “important and independent”. It had arrived at this opinion despite not having received anything more than an executive summary (which it had not read when it agreed to provide “a supportive quote”). It also knew that PHE was far from “independent”, having been made aware of its intention to apply tobacco-style controls to participation in betting and gaming.

At a meeting in March 2022, Gambling Commission officials admitted that they did not understand how PHE had arrived at some of its estimates (no-one could have been expected to – given the fact that the calculations were mathematically incorrect). In April, these officials circulated a highly critical review of the PHE report, in which they noted that the suicide claims were not based on “reliable data”. The Commission however, elected not to take the matter up with the OHID (which had subsumed PHE upon the latter’s disbandment) or to inform the Secretary of State. The market regulator – which counts “doing the right thing” among its corporate values – elected to suppress its critique. In one rather sinister coda to the Commission’s critique, one official speculated that PHE’s claim of more than 400 suicides might be rescued, if only future prevalence surveys showed a higher rate of ‘problem gambling’ in the population. At this point, the Commission had started work on a new Gambling Survey for Great Britain in the expectation that – as a result of methodological issues – would produce a higher rate of ‘problem gambling’ than reported by tNHS Health Surveys.

When asked by journalists whether it considered the PHE claims to be reliable, the Gambling Commission responded that it was not its role to review the work of other state agencies; but failed to mention that this is precisely what it had done. As late as 2023, its chief executive, Andrew Rhodes continued to defend the PHE-OHID estimates, despite being aware of the problems with them; and it seems likely that the market regulator has been involved in disseminating the misinformation via approval of regulatory settlement funds.

2. the ABSG and the irrelevance of accuracy

In the summer of 2022, the OHID wrote to the Gambling Commission’s Advisory Board for Safer Gambling (‘ABSG’) to ask for its opinion on criticism of PHE’s suicide analysis. In her response, the ABSG’s chair, Dr Anna van der Gaag appeared to agree that there were indeed a number of issues. She wrote: “I see their point about basing calculations on the Swedish hospital study leading to an over estimation of the numbers”. She then proceeded to suggest that accuracy in such matters was unimportant and that attempts to apply scrutiny was “a distraction from what matters to people and families harmed by gambling”. This represented a change in attitude from three months earlier when the ABSG had described PHE’s highly exact estimate of 409 suicides associated with problem gambling as a “catalyst towards action”. The Gambling Commission allowed the ABSG to publish this opinion in the full knowledge that it was based on unreliable data.

The following year, Dr van der Gaag was one of two co-adjudicators responsible for allocating around £1m in Gambling Commission (regulatory settlement) funding for the purposes of research into suicide and gambling. Applicants were specifically directed towards the OHID analysis (i.e. estimates that the ABSG knew were flawed) as well as claims by the activist group, Gambling With Lives (despite the fact that even the OHID had indirectly criticised one of GwL’s claims). One of the successful bids (a £582,599 award to a consortium led by the University of Lincoln) included Gambling With Lives as an active member of the research team.

3. the Silence of the ‘Independents’

Among those who have supported the claims of PHE-OHID are a number of self-styled ‘independent’ researchers. These include academics from the universities of Cambridge, Hong Kong, Lincoln, Manchester, Nottingham and Southampton, as well as King’s College, London, who have cited the estimates uncritically in their work. Perhaps they considered (naively, if so) that research produced by the Government is unimpeachable; yet the errors made by PHE-OHID are so glaring that no researcher of any calibre could have failed to notice them. The failure to subject such serious claims to critical analysis before repeating them indicates – at the very least – an absence of intellectual curiosity. Much is made of the need for research independence (typically defined solely by an absence of industry funding, regardless of ideology or other affiliations); but independence has little value if it is not accompanied by intelligence and integrity.

4. Breaking ground

A small number of groups and individuals have been prepared to apply scrutiny and challenge, despite the circumstances. The Racing Post and the think tank Cieo have published a number of our own articles on the problems with PHE-OHID (as well as other issues with research-activism); and a handful of journalists, including Chris Snowdon, Steve Hoare and Scott Longley have been prepared to challenge the PHE-OHID claims. Figures from trade groups, bacta and the Gambling Business Group have spoken out publicly on issues with PHE-OHID.

Officials at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport have displayed a capacity for critical analysis, notable by its absence elsewhere in Whitehall. Their White Paper on reform of the betting and gaming market acknowledged valid concerns about self-harm but conspicuously omitted the OHID figures. Lord Foster of Bath, a stern critic of the gambling industry, has acknowledged that the PHE-OHID claims are not reliable and – in a show of honesty and humility rare in the gambling debate – apologised for using the figures himself. He continues to make the case for self-harm to be treated seriously in a gambling context; but without recourse to spurious statistics. Philip Davies, the Conservative Member of Parliament for Shipley, has challenged unsound statistics in parliamentary debates; and Dame Caroline Dinenage’s select committee for Culture, Media and Sport noted concerns of reliability in its report on gambling regulation.

One member of the Gambling Commission’s senior management team – Tim Miller – has been prepared to discuss and acknowledge problems with PHE-OHID; an attitude that contrasts sharply with that of his colleagues.

5. ‘Noble lies’ and consequences?

Underlying the PHE-OHID saga is a sense that some people in positions of authority consider it acceptable to publish inaccurate or misleading statistics if the cause is – in their opinion – just. Some have even suggested that scrutiny of misinformation is unethical, rather than its manufacture. In July this year, the Gambling Commission intends to publish statistics on the prevalence of suicidality amongst gamblers. Given its role in PHE-OHID (in addition to major issues with its new survey), it is questionable why anyone should consider these results credible. It has also – via Gambling Research Exchange Ontario – sponsored a programme of research into wagering and self-harm. Given that these studies have been explicitly grounded in the PHE-OHID deception – and the complicity of many of those involved – suspicions of bias will accompany publication. It is the publication of unreliable research – rather than scrutiny of those statistics – that undermines public trust in authority. Attempts to address health harms in any domain will be ineffective if they are based on inaccurate evidence.

An independent and open review should be carried out into the PHE-OHID deception; but it is difficult to see how this will happen. The Department of Health and Social Care and the Gambling Commission are unlikely to embrace scrutiny; and the DCMS will not wish to embarrass either its regulator or another government department. There are too many people in Parliament and the media who have played a part; and too few prepared to break ranks. The gambling industry meanwhile (with a number of notable exceptions) has shown little inclination to challenge. There is one hope – that the Office for Statistics Regulation will be prepared to take an interest in the integrity of public health estimates. Such an intervention would go somewhere at least towards restoring trust in public bodies.

Cracking the Code: Exploring the role of the Regulators’ Code in Britain’s gambling market

By Dan Waugh, Regulus Partners

| To what extent should the Gambling Commission be guided by the Regulators’ Code in discharging its duties? To what extent does it comply with the Code and how would we ever know? Does this matter? This is the discussion that we hope to stimulate with the publication today of our new report, ‘Questions of Principle: Assessing the Gambling Commission’s compliance with the Regulators’ Code and the Nolan Principles’. At present, there is considerable uncertainty about what influence, if any, the Code should exercise on the regulation of Britain’s betting and gaming market; and the perpetuation of this uncertainty, we argue, is unlikely to be in the best interests of consumers. The Regulators’ Code was introduced in 2014 by the Department of Business Innovation and Skills. All statutory regulators in Great Britain – including the Gambling Commission – are required to “have regard” to the Code in exercising their duties – a phrase that accommodates a high degree of subjectivity. Last year, the Commission’s chief executive, Andrew Rhodes described the Code as “not a long document – just seven pages”; and “a sensible set of guiding principles” – a characterisation that drew rebuke from the legal community. On leading lawyer responded: “I am sure Andrew Rhodes wouldn’t like to see gambling operators treating, for example, its seven page Industry Guidance on High Value Customers as just a ‘sensible set of guiding principles’”. The exchange highlighted an unhelpful difference of opinion between the market regulator, its licensees and licensing lawyers.  The Code itself consists of six provisions:Regulators should carry out their activities in a way that supports those they regulate to comply and grow;Regulators should provide simple and straightforward ways to engage with those they regulate and hear their views;Regulators should base their regulatory activities on risk;Regulators should share information about compliance and risk;Regulators should ensure clear information, guidance and advice is available to help those they regulate meet their responsibilities to comply;Regulators should ensure that their approach to their regulatory activities is transparent. Regulators are required to adhere to the Code in the context of their wider statutory roles and they may exempt themselves from certain provisions, so long as they explain why. Our analysis suggests that, while the Gambling Commission (which has not announced any Code exemptions) is often compliant, there have been instances where it appears to have breached code provisions, sometimes on a repeated basis. Our report highlights particular concerns with regard to the Commission’s observance of the first and sixth Code provisions – supporting compliance and growth; and ensuring transparency. The first of these Code provisions is often misinterpreted as a requirement for the Commission to encourage economic growth at all costs – something that is clearly incorrect. The provision is however, more nuanced than this. It asks that regulators “avoid imposing unnecessary regulatory burdens”; and that they “assess whether similar social, environmental and economic outcomes could be achieved by less burdensome means”. They should also “understand and minimise negative economic impacts of their regulatory activities”; “improve confidence in compliance for those they regulate, by providing greater certainty”; and “ensure that their officers have the necessary knowledge and skills to support those they regulate, including having an understanding of those they regulate that enables them to choose proportionate and effective approaches.” These are sensible requirements for any market regulator; and yet we were able to find little evidence that the Commission actively pursues them. Its public consultations rarely (if ever) suggest active consideration of the need to understand and minimise regulatory burdens. Last year, the Commission’s chief executive, Andrew Rhodes observed (correctly) that “growth must come when the business is compliant, not instead of it”. This is undoubtedly true, but the fact is that most licensees are compliant (if they were not then they would cease, at some point, to be licensees). No market – even a monopoly – is likely to be 100% compliant all of the time; and it is clearly not the intent of the Code that regulators should withhold support pending universal compliance. It is also unclear why the Commission would see non-compliance as a reason to ignore its duty to “understand and minimise negative economic impacts” of its regulatory activities, or to “ensure that their officers have the necessary knowledge and skills” – particularly when it is often the customer who ‘pays’ for impacts and deficits. Our report highlights a number of instances where the Commission appears to have fallen short of the standards set by the Code. These include:The approval of regulatory settlement grants for organizations and individuals openly engaged in anti-gambling advocacy;The misuse of statistics and research – and the withholding of key evidence -in public consultations on regulatory reform;Inconsistent and often opaque approaches to policy determination (arising from public consultations);A failure to apply evaluation or scrutiny to the award of £90m of regulatory settlements between 2019 and 2023. In addition, as we note in our article for Cieo this week (Help! I have become an ‘issue’ – Cieo), we have uncovered indications of bias within the Commission’s Advisory Board for Safer Gambling, as well as the existence of secret meeting notes which should, in our view, have been published. Any review of compliance is necessarily selective – and no organization is perfect. It is important not to lose sight of the many achievements of the Commission in supporting a generally well-functioning market, characterised by low rates of illegal and underage gambling and a world-leading approach to sports integrity. The rate of ‘problem gambling’ is also very low by international standards, with 0.25% of adults estimated to be PGSI ‘problem gamblers’. This, at least, is the case at present – although the Commission’s plan to replace the ‘gold standard’ NHS Health Survey with its experimental Gambling Survey for Great Britain seems certain to result in much higher – and far less reliable – reported rates of ‘problem gambling’. The Regulators’ Code is a valuable document, designed to help market regulators to focus on their statutory roles, without getting distracted by alternative, often incompatible political agendas. The Commission has the opportunity to make far greater use of the Code by stating explicitly how it guides its strategy; by actively monitoring and reporting on its compliance (as some other regulators do); and by establishing a mechanism for constructive engagement with licensees and others in regard to suspected breaches. The absence of such measures will inevitably give rise to confusion and cynicism – neither of which is in the interests of the consumers who the Gambling Commission was established to serve.Please see our full report here: Questions of Principle: Assessing the Gambling Commission’s compliance with the Regulators’ Code and the Nolan Principles |

| Disclaimer; The analysis provided in this report represents the opinions of the authors. Any assessment of trends and change is necessarily subjective. The information and opinions provided herein are not intended to provide legal, accounting, investment or policy advice, nor should they be used as a forecast. Regulus Partners may act, or have acted, for any of the companies and other stakeholders mentioned in this report. |

| Copyright © 2024 Alpha Leonis Group Limited, All rights reserved. Our registered address is: Suite 1-3 Hop Exchange, 24 Southwark Street, London, SE1 1TY |